Tunnel History

"Over the Last Muck Pile"

View of a group of people stepping over a pile of rubble in the Whittier Tunnel (Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel) during its construction. The man at the front and center of the group is General Simon Bolivar Buckner, and to his right is Colonel Benjamin Talley. Nov. 1942

Project History

As residents and visitors drive to and from Whittier through the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel for the first time this summer, they mark the beginning of another phase in the life of a unique transportation corridor.

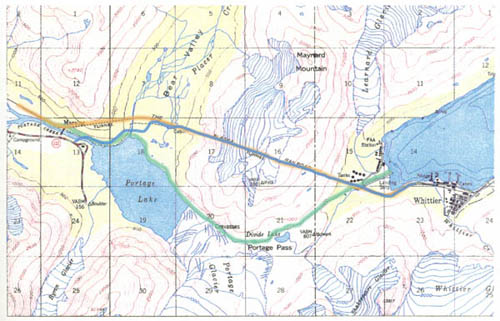

Travel between Prince William Sound and Turnagain Arm has always been a vital part of life in Alaska, although modes and routes have continued to change. Chugach Eskimos have hunted and gathered in this area for thousands of years. They trekked over Portage Pass and Portage Glacier to trade and fight with the Athabaskan Indians of Cook Inlet. Many miners and prospectors also used Portage Pass to reach the gold fields of Cook Inlet and the Kenai Peninsula in the late 19th century. Often dropped off at the head of Passage Canal, these adventurers used pack trains, sleds, and pulleys to drag equipment and supplies over Portage Pass in hopes of striking it rich in Cook Inlet or on the Kenai Peninsula. During this period, Portage Glacier still covered most of Portage Lake. Travelers climbed to Portage Pass and traversed the eastern edge of Portage Glacier to Bear Valley. From there they would walk the front of the glacier onto the base of Begich Peak and drop down to Portage Valley.

This route, however, was both difficult and dangerous. In 1914 the Alaska Railroad Corporation began to consider ways to construct a railroad spur to what is now the town of Whittier. While railroad manager Otto Ohlson championed this route because of its ability to provide a shortcut to a deep-water port (a trip to Seward added 52 more miles), this route didn't become a reality until World War II. The main advantages of using Whittier as a rail port was that it was a shorter voyage, reduced exposure of ships to Japanese submarines, reduced the risk of Japanese bombing the port facilities because of the bad weather, and avoided the steep railroad grades required to traverse the Kenai Mountains.

In 1941, the U.S. Army began construction of the railroad spur from Whittier to Portage. This line became Alaska's main supply link for the war effort. Anton Anderson, an Army engineer, headed up the construction. The tunnel currently bears his name.

Left: Steam locomotive traverses Bear Valley shortly after the tunnel opens.

Right: Alaska Railroad Whittier shuttle passes stockpiles of stone needed for new track and road.

On April 23, 1943 workers completed the spur, which consisted of a 1-mile tunnel through Begich Peak and a 2.5-mile tunnel through Maynard Mountain, thus linking Whittier to the Alaska Railroad's main line at Portage.

With a new rail connection to Whittier, the area began to change. In the mid-1940s, work crews and supply ships began to arrive, and population, including military and civilian personnel, swelled to over 1,000. Infrastructure—such as buildings (including the six story Buckner building and the Begich Tower), a power plant, and a petroleum tank farm—began to change the landscape.

The 1950s brought change to Whittier once again. As the military pulled out, Whittier transformed into a federally run commercial port. This turn of events also provided the opportunity for the private ownership and development potential that exists today.

Growing demand for access to Whittier spurred the DOT&PF to link

the community to the highway system.

Whittier's geographical location makes it the ideal gateway for freight ships, cruise lines, fishers, and recreational boaters. The beauty of Prince William Sound attracts tourists every year. Whittier has been a port on the Alaska Marine Highway, but its only link to Alaska's highways was via the Alaska Railroad. The Alaska Railroad began offering a shuttle service between Portage and Whittier in the mid 1960's. This unique form of rail service allowed vehicles to drive on to flat cars to be transported between Whittier and Portage. As the numbers of people traveling to and from Whittier increased, so did the demand for more convenient and affordable passage to Whittier. Studies conducted make clear that there is more demand for access than can be accomdated with the Alaska Railroad's shuttle operation. This need spurred the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF) to search for a way to improve this transportation corridor. The DOT&PF considered several options, including:

- Increasing the conventional rail service

- Using a high-speed electric train service

- Constructing a highway route over the mountain

- Constructing a highway route through the tunnel

- Constructing a highway to Maynard Mountain and engineering the 2.5 mile long tunnel to accommodate both a roadway and a railway.

After studying all the options, DOT&PF, in consultation with the Alaska Railroad, the public, and tunnel, railroad, and highway experts, determined that the best solution was to construct a highway to Maynard Mountain and transform the existing railroad tunnel into a one-lane, combination highway and railway tunnel that allows cars and trains to take turns traveling through the tunnel. HDR Alaska, on behalf of the DOT&PF, prepared the "Whittier Access Project Environmental Impact Statement," an environmental analysis required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) approved the environmental impact statement (EIS) in November 1995.

DOT&PF contracted with CH2M Hill to design the approaches and the bridges to the tunnel facility. This project consisted of 1.5 miles of road, one 500 foot long tunnel and two bridges from the Portage Glacier Highway near the Begich-Boggs Visitor Center to the Bear Valley staging area. Herndon and Thompson, Inc. constructed this project.

DOT&PF chose the project as its first design/build project. HDR Alaska was contracted to produce a conceptual design, write the performance specifications on which the final tunnel design was based and assist DOT&PF manage the construction contract. HDR brought together nationally recognized experts in design/build law, tunnel engineering, ventilation, tunnel control systems and railroad and railroad signal systems.

In June 1998, DOT&PF awarded the tunnel contract to Kiewit Construction Company, who then selected the firm Hatch Mott MacDonald to design the project. As part of this design-build contract, the Kiewit team worked out a preliminary design for each component of the project with "over the shoulder review" from DOT&PF and HDR Alaska. The project consisted of more than 50 separate design and construction tasks, and construction began in September 1998.

This unique facility meets all requirements for safety. Its design and construction will benefit all State of Alaska constituents and will provide the efficient and affordable access to Whittier and Prince William Sound that people have long sought.

Whittier small boat harbor

For details on design and construction, see the Tunnel Design page in this website.

The Tunnel

- Whitter Access Tunnel Home

- Schedule & Hours of Operation

- Accomplishments

- Virtual Drive

- Vehicle Size, Tunnel Restrictions

- Tolls

- Project History

- Design

- Construction Photos

- Operations

- Traffic Data

- Motorcycle Safety Information

- Regulations

- FAQs

- Weather

- Current Weather

- FAA Weather Cams

Related Resources

- 511.alaska.gov -

Traveler Information - Alaska Railroad Corp.

- Alaska Marine Highway

- Chugach National Forest

- Chugach Alaska Corp.

- City of Whittier