How are speed limits set?

What do speed limits mean and why are they important? Speed limits are posted to inform drivers of the maximum speed considered safe and reasonable under good conditions when the pavement is dry, the road is in good repair, and the weather is clear. That means when it’s raining, snowing, icy, or other potential hazards are present, you will likely need to slow down. Regulation in the Alaska Administrative Code (13 AAC 02.275) states “no person may drive a vehicle at a speed greater than is reasonable and prudent considering traffic, roadway, and weather conditions.”

Reasonable speed limits lessen the difference in speeds between vehicles, which reduces the potential for conflicts between vehicles.

After first using your own judgment to slow down for conditions, posted speed limit signs are another way to otherwise know the maximum speeds at which you should be driving. Alaska Administrative Code (13 AAC 02.275) also sets basic guidelines for maximum speed limits on different types of roads:

- 15 miles per hour in an alley

- 20 miles per hour in a business district

- 25 miles per hour in a residential district

- 55 miles per hour on any other roadway

When are maximum speed limits re-evaluated?

Posted speed limits can be re-evaluated in two ways:

- when a department project redesigns the roadway, or

- when there is formal community support to re-evaluate the current posted speed limit.

A change in speed limit from the maximum speeds above requires an engineering study or a new general regulation. There are many factors considered in the engineering study in accordance with the law under state statute AS 19.10.072(b).

What factors are involved?

The maximum speed limits listed above apply to most roads. DOT&PF has an established process for determining if a different speed limit is appropriate for a given section of road. When DOT&PF staff investigate a speed limit they may schedule an in-depth speed study. A speed study is an engineering and traffic investigation that considers:

DOT&PF staff install new speed signs on the Richardson Highway in 2016 after a speed study determined the speed limit should be changed from 55 miles per hour to 60 miles per hour between Fairbanks and North Pole. Photo by DOT&PF Staff

- Physical characteristics of the road (width, curvature, grade, or sight distance)

- Potential conflicts between different types of road users (pedestrians, bicycles, children)

- Type and level of land use adjacent to the road (schools, residences, crosswalks, parks)

- Potential conflict between drivers (driveways, parking, turning locations)

- Crash history (types of crashes, frequency, severity)

- Enforcement feasibility and effectiveness (Alaska State Troopers, local police departments)

- Community input (cities, boroughs, community councils, community organizations)

- Federal and state regulations

- Current driver speeds

These considerations are all important factors in a speed study. They illustrate the extent of conflicts present. For example, if there are many active turning points (driveways and side streets) along a road, there are more opportunities for conflicts between turning traffic and through traffic. There may be more conflicts present if the area has many pedestrians, bicyclists, and school children from development near the road. Crash history may also point to past problems. Roadway geometry (straight, curves, shoulders) affects speeds. Enforcement feasibility is an important factor as well. All these factors combined could lead to a lower or higher posted maximum speed limit.

Summer evening traffic heads to Anchorage on the New Seward Highway. Photo by H.M. (Butch) Douthit, Alaska DOT&PF

How are speeds measured?

DOT&PF staff typically use radar speed equipment to collect speed measurements of free-flowing traffic on the roadway when conditions are ideal—that is, when the pavement is dry and traffic is low during “off-peak” hours (not during morning, lunch, or evening rush hours). Staff avoid counting vehicles that are being held up by those in front of them, slowing down for a red traffic signal, or making a turn. The idea is to observe speeds that include “everyday” drivers who are choosing the speed they feel is appropriate. Data may be collected at multiple points along the route and on multiple days.

What are common results?

When hundreds, or sometimes thousands of motorists are sampled, the data tends to show consistent, repeatable results, even years later. Most drivers are observed to be careful, reasonable, and prudent. They are a common group of law-abiding, courteous drivers. There are other drivers whose speeds are well above or below the majority of drivers. This includes some reckless and aggressive drivers who disregard speed limits and may only be affected through aggressive enforcement. Additionally, there are very slow drivers who may significantly impede the normal flow of traffic. One way to influence these fast and slow drivers is through coordinated education, enforcement, and engineering strategies.

Why does it matter how fast everybody is driving?

The range of speeds at which people currently drive is an important factor to examine when conducting a speed study. If speed limits are set far beyond or below the speed at which most people drive, this could create a large speed difference between vehicles that could create its own safety issue.

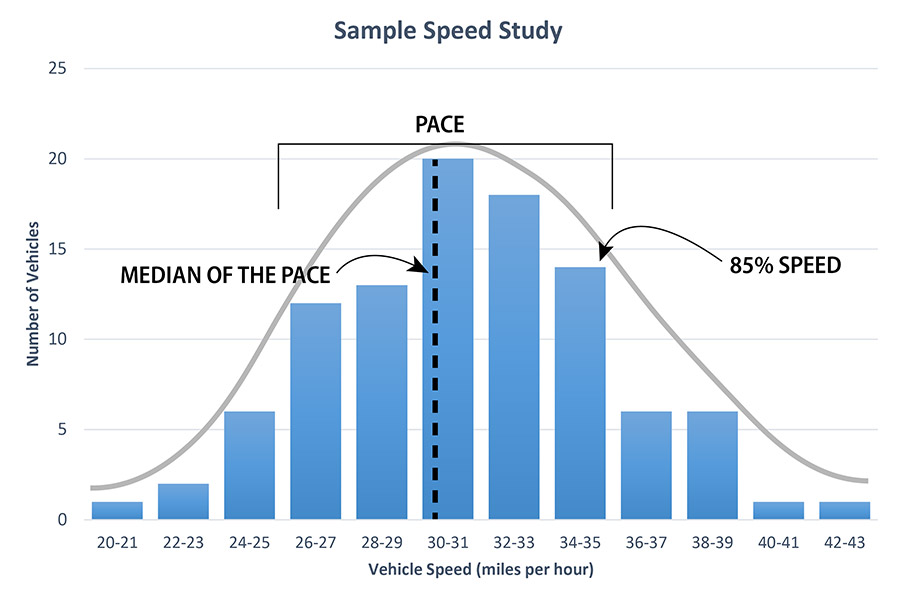

Given most drivers select safe speeds, traffic engineers look at the speed data they have collected to figure out the pace, which is the 10-mile-per-hour range that includes the largest number of vehicles, and the 85th percentile speed, which is the top speed that 85% of drivers were traveling at or below. These two measures indicate expected compliance with posted speed limit signs and existing road conditions, and help to determine whether additional measures are required.

The speed data collected shows a common pattern of behavior and outliers, usually in the form of a table or bell curve. For example, the following data shows the number of vehicles that clocked in at each speed, rounded to the nearest two mile-per-hour interval. In the last column, the number of vehicles at each speed is added to all the ones in the rows above it to see what percent of vehicles were driving at or below a given speed.

Speeds (MPH) |

Frequency of vehicles at this speed |

Cumulative percent of total vehicles at or below this speed |

|---|---|---|

20-21 |

1 |

1% |

22-23 |

2 |

3% |

24-25 |

6 |

9% |

26-27 |

12 |

21% |

28-29 |

13 |

34% |

30-31 |

20 |

54% |

32-33 |

18 |

72% |

34-35 |

14 |

86% |

36-37 |

6 |

92% |

38-39 |

6 |

98% |

40-41 |

1 |

99% |

42-43 |

1 |

100% |

Pace

The pace is found by identifying the 10-mile-per-hour range that includes the largest number of vehicles. In this sample, the range between 26 miles-per-hour and 35 miles-per-hour includes the largest number of vehicles: 77 vehicles. Next, the median of the pace (the middle of a group of numbers) is 30 miles-per-hour.

The median of the pace is important because DOT&PF policy requires the posted speed limit be at or near that number, after adjusting for local factors. If a speed limit was posted below the median of the pace, it could create more variability among motorists’ speeds, which creates conflicts between drivers that can lead to reduced safety.

85th Percentile Speed

In order to determine the 85th percentile speed, engineers round to the nearest five miles-per-hour. For the table above, the 85th percentile speed is between 32 and 34 miles-per-hour, which we can round to the closest increment of either 30 or 35 miles-per-hour, depending on the amount of data in either direction.

Posting a speed limit at or near the 85th percentile speed means the majority of motorists should be able to easily comply without significant changes in the roadway or other coordinated efforts. Just as with median pace, setting a limit too far below the 85% speed could increase variability among driving speeds.

Are current driver speeds the only factor?

No. Current driver speeds are an important factor in determining speed limits, and can be one of the more complicated factors to understand, but it is not the only consideration. Other factors in context with the area as noted above will reflect increasing activity and conflict which can lead to lower speed limits. Speed limits can also be lowered in order to form a transition from rural to urban speed zones.

How effective are speed signs?

Studies have shown that drivers generally will choose the speed that gets them where they’re going as quickly as possible without endangering themselves, others, or their property. Posted speed limits are one factor, but not the only one, and not the most important one when it comes to the speed people drive.

According to a report published by the Federal Highway Administration that looked at driver behavior and crash data from 100 sites in 22 states where speed limits had been lowered or raised, changing speed limits had little effect on how fast people drive. One of the conclusions of the report states, “Changing speed limits alone, without additional enforcement, educational programs, or other engineering measures, has only a minor effect on driver behavior.”

Lower speed limit signs and adding more speed limit signs are not always the most effective tool. Alaska has experience in corridors where lowering speed limits has worsened the pace and the speed differential between motorists. Speed limit signs were then viewed as unreliable or objectionable, leading to disregard and reduced effectiveness. Instead, other tools like increasing law enforcement presence, educating drivers on the risks of speeding in a particular corridor, or changing the design of a roadway can be more effective.

For more speed limit information:

Changing a speed limit takes a lot of research, data collection, and written analysis to be credible and legal. When DOT&PF staff are contacted by citizens requesting a speed limit change, DOT&PF staff typically recommend the requestor work with their local government or community council to gauge broader public support before submitting a request. This helps DOT&PF prioritize limited operational resources.

If you would like to contact DOT&PF about changing a speed limit, please contact one of the DOT&PF regional traffic and safety engineers:

Central Region (Anchorage, Matsu, Kenai):

Anna Bosin, P.E., (907) 269-0639, anna.bosin@alaska.gov

Northern Region (Fairbanks, Delta Junction, Tok, Valdez):

Nathan Stephan, P.E., (907) 451-5381, nathan.stephan@alaska.gov

Southcoast Region (Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Kodiak):

Nathan Purves, P.E., (907) 465-4521, nathan.purves@alaska.gov