Alaska Highway 75th Anniversary - 2017

Today it seems logical that there would be a road connecting the 48 contiguous states with their continental sibling to the north. The idea of connectivity in the modern age is a forgone conclusion with some of the most remote areas in the Last Frontier being fully integrated into the digital age.

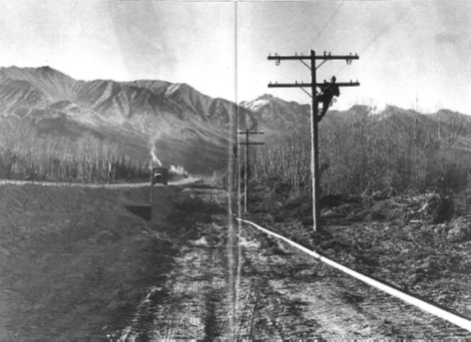

The biggest surprise on the Alaska Highway project was the ability of modern American equipment to make short work of excavating the highway across

mountains, which a few years previous would have required expensive and time-consuming tunneling. This photo shows the pioneer road before the grade

was dropped another 22 feet. (Photo and caption courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014.)

It has been 75 years since the Alaska Highway — the most expensive World War II project taken on by the United States government, in cooperation with the Canadian government — was completed. In an instant, this territorial outpost of the U.S. was recognized as an important strategic defense position against a potential Japanese invasion of the North American mainland. The result was a monumental effort that combined military and civilian workers in the United States and Canada.

Early Stages

Surveying party marking centerline during the winter of 1942 (Photo courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014)

The first serious proposal of a road between the then-Territory of Alaska and the United States was offered in 1929. The International Highway Associations, comprised of representatives from Dawson City, Yukon Territory; Vancouver, British Columbia; Seattle; and Fairbanks, Alaska, convened to lobby Congress for this new access to the North. The results of a feasibility study in 1930 determined the road was feasible and could be built at a reasonable cost. However, arguments over the proposed route and funding over the next decade resulted in no substantive progress on the road.

Initially, the Alaska Highway was built to service the military outposts that dotted the landscape of Alaska and provided much needed support in the form of airplanes and other military supplies to the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease Act passed on March 11, 1941. With the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States was officially thrust into World War II. No longer was the U.S. just supplying aid to the Allies and sitting on the sidelines. A need to protect U.S. mainland and territorial interests became a reality that devastatingly hit home.

For the first few months of construction, the engineers had only manpower to blaze the trail for the Alaska Highway.

(Photo courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014)

Construction of the Alaska Highway officially began March 11, 1942, about 90 days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The initial shipments of construction equipment came by boat into the port of Valdez and by air to the various Northwest Staging Route airfields. These first shipments consisted of 174 steam shovels, 374 blade graders, 904 tractors and more than 5,000 trucks. These also included countless bulldozers, snowplows, cranes and generators. Two-hundred and fifty thousand tons of materials and 10,000 soldiers began the leap frog construction of the road. The bombing of Dutch Harbor, Alaska, by the Japanese on June 3-4, 1942, made all too real the threat of a mainland invasion.

Until heavier equipment arrived, the engineers had to be creative, using local supplies to continue construction. Here, a D-4 dozer pulls a makeshift

grader crafted from local timber. (Photo and caption courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014.)

Other Projects In the Area

What is often overlooked is the Alaska Highway also was used as a corridor for two other concurrent wartime construction projects: the Canol (Canadian Oil) Pipeline and the Alaska Military Highway Telephone and Telegraph Line (AMHTTL).

Canol, Alaska Highway, and AMHTTL, ca. 1942 (From Haigh (2001:108-109). Original in collection at Anchorage Museum.)

Construction of the 4-inch Canol Pipeline began in June 1942. The Canol military oil supply line, which started at Norman Wells in the Northwest Territories, met up with the Alaska Highway at Johnson Crossing. The oil was sent on to Whitehorse, Yukon Territories, where it was refined and continued west into Alaska providing fuel to the Northwest Staging Route airfields ending at Ladd Airfield in Fairbanks. The Canol ceased operation in 1944 but was replaced by the 8-inch Haines-Fairbanks Pipeline (H-F Pipeline), a multi-fuel line servicing the permanent Interior Alaska military installations. The H-F pipeline began operation in 1955 and was abandoned in 1971. The H-F pipeline also took advantage of the corridor created by the Alaska Highway using a similar footprint as the Canol for its location.

The need for secure, reliable communication was another of the Army’s concerns. The Alaska Communication System (ACS), which began as the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System, had served Alaska since its completion in 1905. It was overwhelmed by the increase in telephone and telegraph transmissions. Magnetic and atmospheric interference common in the northern latitudes caused wireless radio communication to be unreliable. For these reasons, beginning in June 1942, the U.S. Army Signal Corps, using mostly civilian contractors, installed the Alaska Military Highway Telephone and Telegraph Line, which started in Edmonton, Alberta, and ended at Ladd Airfield. As might be expected, the Alaska Highway corridor was the natural location for the portion of the line beginning in Dawson Creek, British Columbia. Portions of the AMHTTL can still be seen along the Alaska Highway today, with the most visible sections of the AMHTTL in Alaska occurring east of Northway Junction.

Upgrading the Pioneer Road

Muskegs are like a muddy version of quicksand. A vehicle would pass through a muskeg once, but within a short time, the area would turn into liquid mud,

losing strength. Once caught, a vehicle had to be pulled out. (Photo and caption courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014.)

Since its initial completion as a pioneer road by the Army Corps of Engineers on Nov. 20, 1942, the Alaska Highway has undergone continuous revision. What was initially a muck bog or muskeg required the placement of on-site available trees to create a corduroy road over the thawing permafrost to the introduction of dirt and gravel surface before it was actually passable by vehicle in 1943.

Example of a corduroy road (Photo courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014.)

The U.S. Public Roads Administration (PRA) assumed maintenance and engineering responsibilities after the initial trail blazing by the Army Corps of Engineers regiments. The pioneer road width was only 12 feet with 3 foot-shoulders and 10 percent maximum grades. The PRA widened the finished road to 24 feet, with 6-foot shoulders and 7 percent maximum grades a year later. The compacted earth and makeshift corduroy roads were replaced by 2-foot-thick crushed stone and gravel. Log box culverts and wooden stave pipe culverts were used to traverse the small streams to provide drainage to lessen the seasonal flooding of the road. One-way temporary bridges gave way to steel permanent structure as the road’s shoulders and grades were “smoothed out.”

Wooden stave pipe culverts were the most common type used on the Alaska Highway, usually fashioned by the engineer regiments’ saw mill companies.

(Photo and caption courtesy of Missouri University of Science and Technology 2014.)

In 1943, five permanent bridges were constructed over the major water crossings on the Alaska Territory portion of the highway under the PRA. The Tanana River Bridge, the Tok River Bridge, the Robertson River Bridge, the Johnson River Bridge and the Big Gerstle River Bridge (later renamed the Black Veterans Memorial Bridge) were all constructed and put in place during the first major revision, realignment and stabilization of the road. Of these bridges, four are still in place in their original locations even as the path of the road has been modified throughout the past 75 years. All of these bridges were determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places due to their connection with the construction of the Alaska Highway.

The Tanana River Bridge was replaced in 2010, and the Tok River Bridge is scheduled for replacement within the next two years. It is likely in the coming years all of the original permanent bridges will be replaced. Upon replacement of each bridge, plans to memorialize the construction of the bridges and the Alaska Highway itself near the bridges’ original locations and along the road at pullouts and recreation sites are in the works.

Opening to the Public

Advertisement for the first commercial “Pleasure” trip up the Alcan Highway in 1948

The opening of the Alaska Highway to civilian non-military use officially started in 1948 when Greyhound tour buses braved the primitive conditions to bring adventurous people to the Last Frontier. However, there are well documented accounts of the Cotter and Hayes families, from Arkansas, and L.D. Roach, of Seattle, receiving permission from the Canadian government in 1946 and setting out on the road to homestead in Alaska.

The straightening of dangerous curves and the widening of the road surface for modern transportation has been an ongoing process. Abandoned sections of the pioneer road, as well as other early segments of bridges, are visible in places. Most of the remnants of the Canol and Haines-Fairbanks pipelines have long been removed and scrapped. The corridor for those is still visible and used for ATVs and snowmachines by people living in the Native villages near the Alaska Highway and the towns, such as Tok, that were a product of the road’s creation.

Spring breakup on the Alaska Highway, ca. 1946-1960 (Photo by U.S. Army Engineer District, Alaska. Anchorage Museum, Cook Inlet Historical Society

Collection, B1962.x.15.8)

The Alaska Highway has been a work in progress for the past 75 years. Paving of the entire Alaska section of the highway was completed in the 1960s. Permafrost, floods, fires and earthquakes have all left their marks on the road. Work will continue into the future as additional passing lanes, adjustment of road curves for increased safety and the replacement of the original steel bridges bring the road up to 21st century standards. The ever changing environmental conditions and transportation needs will continue to shape the future path of the Alaska Highway. Although the Alaska Highway of today might not physically resemble the pioneer road, it still serves its original purpose of providing a land-based connection to move goods and people between Alaska and the 48 contiguous United States.

Responsibility for the road has moved from Public Roads Administration and the Bureau of Public Roads when Alaska was a territory to the Alaska Department of Highways upon statehood in 1959 working under the Federal Highway Administration in 1967 and now to the current Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF). With funds from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), DOT&PF is now charged with the maintenance and repairs of the Alaska Highway. It is part of our mission to keep Alaska moving through service and infrastructure on the Alaska Highway for the next 75 years and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE: Adobe Acrobat PDF files require a free viewer available directly from Adobe.